Facades: Grand Tour

By ROBERTA SMITH APRIL 4, 2018

Wells Cathedral Church of St. Andrew, 2015-2016, by Markus Brunetti. Credit Markus Brunetti/Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Markus Brunetti’s enormous photographs pack a healthy jolt of wonder, something more likely felt in the 19th century, when the medium was invented. I felt some of it in 2015 at “Facades,” Mr. Brunetti’s American debut at the Yossi Milo Gallery. It’s still palpable in this second show there, “Facades — Grand Tour,” through April 14.

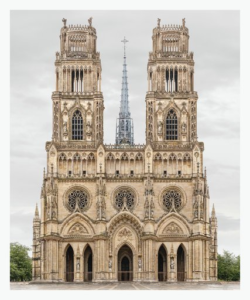

Orleans Cathedral, 2008-2016.

Mr. Brunetti, who was born in Germany in 1965, had worked for about two decades in advertising when, in 2005, he switched to a more singular vocation. He became an itinerant photographer of one of photography’s oldest subjects, the religious architecture of medieval Europe, and used the latest technology to capture the facades of these landmarks with an astounding clarity of detail.

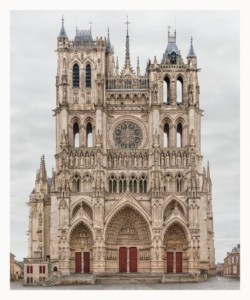

Amiens Cathedral, 2009-2016.

Mr. Brunetti began traveling around Europe with his partner, Betty Schoener, and what the gallery calls “a self-contained computer lab on wheels,” making color images of cathedrals, churches and cloisters mostly from between the 11th and 14th centuries. The structures are very large, and so are the images — up to 10 feet tall.

Trani Cathedral, 2014-2018.

The wonder lies in giving the eye more than it can see. The facades are recorded one square meter at a time, from a fixed position; then these tiny images — from 1,000 to 2,000 — are painstakingly stitched together. The final photograph has a bracing sharpness. Every feature is visible, from the narrative reliefs above the main doors to the gargoyles and spires high above, to the color and textures of the stone.

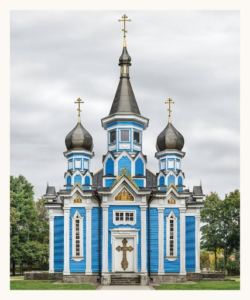

Joy of All Who Sorrow Church in Lithuania, 2016-17.

But that is only part of an uncanny, total focus, which cannot be experienced in real life (except perhaps by insects with compound eyes). Mr. Brunetti’s images are more aggressive than most because his subjects ignore perspective. His church towers do not lean back into the sky as they would if you were looking up at them or seeing a photograph made in a single shot. The lack of normal optical recession gives them an implacable, almost physical presence, especially the really tall cathedrals of Wells, Somerset, England; Orleans, France; or Nuremberg, Germany.

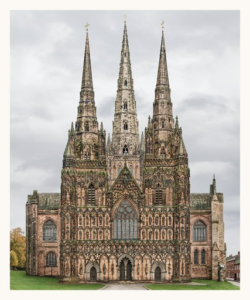

Lichfield Cathedral, 2014-2017.

These photographs are like an architect’s elevation drawings, only much more solid. They also convey how the cathedrals once sat, and in some cases still do, above their towns and cities like large, protective beasts. Some of the buildings come to feel like the architectural equivalents of Barney. You may want to hug them.

Precedents for Mr. Brunetti’s work include the Conceptual German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, who spent nearly five postwar decades documenting industrial structures, from shaky coal-mine winding towers to immense grain elevators. August Sander’s prewar portraits of people from different German professions have a similar typographical ambition. But Mr. Brunetti’s images have their own intense emotional resonance — the buildings are formidable expressions of collective faith made all the more so by their stalwart refusal to bend to perspective.

This show is a chance to get your European church styles down. There’s one example of Romanesque, the Trani Cathedral, in Apulia, Italy, its plain stonework standing in stark, even disapproving contrast to almost everything else here, including the much more ornate cathedral in Siena, Italy, which is Romanesque Gothic.

Then it’s mostly Gothic and High Gothic, when the churches reached unprecedented heights in the naves and spires, thanks to the distribution of weight made possible by the Gothic arch (and flying buttresses, like those on the beautiful Flamboyant Gothic Church of the Holy Trinity, in Vend?me, France). You see how the sumptuousness of the style made the cathedrals more welcoming and urban. Their many sculptures turned them into bibles of stone while the ribbing and traceries added amazing decorative energy.

Cathedrals were meant to enthrall and awe, so the flock would never turn away from God. But temptation is not absent. It is sometimes a little startling to see that the traceries in the windows — rose and otherwise — of cathedrals like Amiens and Vend?me are alive with sinuous curves, arabesques and biomorphic shapes that could be given bodily interpretations. Freed of the imperatives of stone narratives, the builders may have seen the windows as a chance to head out on their own, in the direction of Art Nouveau.